Thomas Sowell’s Wishful Thinking about Race

Blaming “culture” for racial disparities is scientifically wrong and politically unhelpful

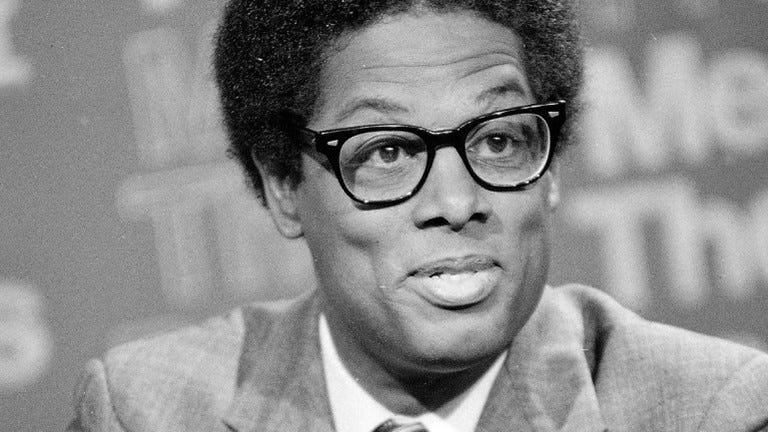

Thomas Sowell is a charismatic speaker and indefatigable writer, publishing almost a book a year (currently 60 and counting). Practically every American intellectual on the right has been influenced by him in some way. For me, his most important work was A Conflict of Visions, which presents a unified field theory of political orientation.

As one of the few intelligent, non-grifter conservatives to rise to prominence, Sowell has guided hundreds of thousands if not millions of people in a better direction. He is a brilliant advocate for libertarian economics and a wise social commentor. However, he can sometimes be tendentious, and that’s particularly the case when it comes to his theory of race differences.

What accounts for persistent racial disparities? There are three serious possibilities: racism, genes, or culture. Wokesters say it’s all white racism, ignoring the many, obvious problems for this thesis. (For example, whites in the US are outperformed when it comes to IQ, income, education, and law-abidingness by several other groups including Indians and East Asians.) Hereditarians say that disparities stem in large part from innate differences in the distribution of traits. (This is my view.) Cultural theorists say that entrenched cultural practices cause races to diverge in their thought and behavior, leading to differences in outcome that cannot be blamed on racism.

Sowell is the leading conservative proponent of the cultural explanation. In regard to race differences in the US, his idea is that black Americans adopted a dysfunctional culture from white rednecks in the South. A different culture would have, and in the future could, set blacks (as well as southern whites) on a different path. While he mostly avoids ad hominem attacks against hereditarians, he portrays most of them as bumbling half-wits with a history of making baseless and contradictory claims.

I was recently interviewed for “The Genius of Thomas Sowell” podcast to talk about hereditarianism vs. culturalism, and the host, Alan Wolan, persuaded me that it would be worth spelling out my objections to Sowell in more detail. Here I respond, in turn, to Sowell’s arguments for the cultural theory of race differences and his critique of hereditarianism. I contend that hereditarianism remains by far the most plausible explanation for persistent gaps among groups living under comparable conditions, including American blacks and whites.

Some hereditarians believe that, even if Sowellism is false, it would be politically expedient to promote it as a means of countering leftist narratives about race and racism. I will explain why this is a mistake. Even if (counterfactually) we could convince large numbers of people to accept Sowell’s scientifically incorrect theory of race differences, this would not stop wokism.

Black Rednecks: The Cultural Theory

Sowell presents his cultural theory of race differences in “Black Rednecks and White Liberals,” which is the first chapter of a book of the same name published in 2005. In his view, African Americans adopted the culture of white rednecks, which

included an aversion to work, proneness to violence, neglect of education, sexual promiscuity, improvidence, drunkenness, lack of entrepreneurship, reckless searches for excitement, lively music and dance, and a style of religious oratory marked by strident rhetoric, unbridled emotions, and flamboyant imagery. (p. 6)

Apparently, many conservatives who think it’s too offensive to say there’s a natural 15-point IQ gap between blacks and whites believe it is fine to tell blacks that they are lazy, violent, promiscuous, improvident, drunk, and reckless, but for cultural reasons.

Sowell argues that redneck culture was imported from the lawless border regions and backwaters of Britain from which the majority of colonial settlers in the South emigrated: the Scottish Highlands, Ulster, Wales, and the northern and western uplands of England. He notes that American Southerners exhibited the same behavioral patterns and were stereotyped in exactly same way as their cousins back in Sticksville, Britain. “Very similar kinds of comments were made about these Southerners’ ancestors in the parts of the British Isles from which they came” (p. 18). In contrast, New Englanders received their culture of temperance and education from their ancestors in the southeast lowlands, which happened to be the center of English civilization.

When people resemble their ancestors, the hereditarian, of course, has a potential explanation. People inherit genes from their ancestors, and genes may be causally linked to certain outcomes. When we’re considering traits that are known to be heritable, such as intelligence, and when group differences persist across long stretches of time and under a range of environmental conditions, the hereditarian thesis needs to be taken seriously.

White hillbillies and Boston Brahmins, southern Negros and black Yankees: Not all “white” or “black” people are the same

Sowell writes: “clearly neither racial discrimination nor racial inferiority can explain similar differences between whites in the North and the South in earlier centuries” (p. 23). This is a misunderstanding that comes up repeatedly in “Black Rednecks and White Liberals.” Hereditarianism is not the thesis that there is an intrinsic connection between skin color and intelligence, or that all “white” or “black” populations are the same. Groups of “white” or “black” people can vary in their average intelligence for genetic reasons.

In an endnote, Sowell writes:

Arthur Jensen has suggested that particular regional subgroups of Southern whites might be biologically less capable mentally as a result of in-breeding, especially “relatively isolated groups in the ‘hollows’ of Appalachia.” Arthur R. Jensen, Educability and Group Differences, p. 61. But this seems hardly likely to account for lower mental test scores for whites in whole Southern states. (endnote 121)

In fact, Jensen says nothing about inbreeding on p. 61 of Educability and Group Differences, or in the surrounding text. Even if you (in my view mistakenly) read the phrase “relatively isolated groups” as an allusion to inbreeding, this still wouldn’t support Sowell’s objection. Jensen observes that “genetic differences in intelligence among subgroups of the white population are no less improbable than differences among racial groups.” On the preceding page, Jensen refers to “the fallacious belief in racial genetic homogeneity” that gives rise to “the notion that regional differences in IQ among whites must be entirely environmental and therefore, if they are of considerable magnitude, can be pointed to as evidence that racial differences must also be entirely environmental.” Sowell seems to have completely missed Jensen’s important point that not all populations drawn from the same race are identical, and falsely assumed that he was arguing that the IQ deficit among southern whites can only be due to inbreeding.

Another observation made by Jensen, which Sowell doesn’t mention, raises a serious challenge for the cultural theory. Sowell touts the fact that that blacks in four northern states averaged higher scores than whites in four southern states on the Army Alpha test administered to recruits during World War I (pp. 23, 31). However, as Jensen notes, within each state, the black–white gaps tended to be around the same as the gap between blacks and whites in the country as a whole. Pennsylvania blacks had higher Army Alpha scores than Mississippi whites, but much lower scores than whites from the same state. Sowell argues that northern blacks outscored southern whites because they adopted the culture of their northern white neighbors. But if culture determines IQ, why didn’t Pennsylvania blacks score the same as Pennsylvania whites?

The obvious hereditarian explanation for the relatively high IQs of northern blacks—particularly in the early twentieth century—is selective migration. That is, the most intelligent blacks in the South were most likely to move North. Although their IQ was below average compared to the relatively elite whites among whom they now lived, it was higher than that of the blacks (and in some cases even the whites) they left behind.

Blacks living in the North in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were either freed slaves or their descendants, many of whom were mulattos (mixed race). Sowell acknowledges this openly:

As a group, the “free persons of color” also differed from the slaves in racial mixture....While only 8 percent of slaves met the stringent U.S. Census requirement of half or more white ancestry to be classified as mulatto, 37 percent of the “free persons of color” did....[T]here were very noticeable skin color differences between the more acculturated descendants of those freed before the Civil War and those freed as a result of the Emancipation Proclamation. (p. 43)

As examples of prominent black leaders in this category, Sowell mentions W. E. B. Du Bois, Timothy Thomas Fortune, Charles Waddell Chesnutt, Thurgood Marshall, and John Hope Franklin—all of whom besides Franklin had obvious, substantial European ancestry.

Sowell asserts that “the historical and cultural antecedents of [the] success [of the descendants of slaves freed before the Civil War] are undeniable,” and refers to “the cultural head starts of this segment of the black population.” I cannot detect any actual argument for this conclusion, which, for some reason, Sowell seems to regard as self-evidently correct. The antebellum freed slaves were (on average) biologically and even racially different from those who were freed after the Civil War. Their success does not pose a challenge for hereditarianism.

“Black” intellectuals Charles W. Chesnutt (left) and Timothy Thomas Fortune (right) illustrate how African Americans can succeed when they have a “cultural head start,” according to Sowell.

Sowell then argues that “the later rise of other blacks to similar levels of achievement undermines the biological explanation of these internal differences among blacks.” This is a non sequitur. Hereditarianism does not say that there cannot be examples of high-IQ blacks even from the less elite population that wasn’t freed until 1865. (I believe Sowell himself is a member of this group.) But higher-IQ populations tend to produce a greater number of such examples.

Sowell’s misunderstanding of hereditarianism is revealed further in the following passage:

Among nineteenth-century Negroes in Philadelphia,...there were major behavioral differences between [mulattos and blacks]. The mulatto neighborhoods had lower crime rates and a higher percentage of their children attending school, as compared to the black neighborhoods, even though it can hardly be claimed that school attendance or crime rates are genetically predetermined. In short, there were major cultural differences—and these differences in turn produced other differences, such as a higher occupational status, better housing, and more wealth among the mulattoes. Nor was this pattern confined to Philadelphia. All across the country, North and South, the elite of the Negro community were lighter in complexion than the masses—and very self-conscious, and sometimes snobbish, about that fact. (p. 44)

Sowell’s chain of reasoning goes as follows: (1) crime rates and school attendance aren’t “genetically predetermined”; (2) mulatto and black communities differed in these outcomes; (3) therefore the differences between the populations must be due to culture rather than genes. But this is a mistake. Outcomes such as being a mugger or going to school aren’t “genetically predetermined,” but they can be influenced by heritable traits. Assuming there was a ~10 point IQ gap between northern mulattos and blacks, you would expect different behavioral patterns with respect to crime and education in exactly the direction that we observed.

Another argument Sowell makes relies on the same mistake that all “black” populations must have the same innate potential. In the mid-twentieth century, blacks who had immigrated to the US from the West Indies had better outcomes than native-born blacks. (Sowell’s data are actually restricted to immigrants from the English-speaking Caribbean.) Among inmates in Sing Sing prison in New York State in the early 1930s, West Indian blacks were underrepresented while native blacks were significantly overrepresented. West Indians were more likely to work in higher skilled jobs. In 1970, all black federal judges in New York were from this demographic. The average income of West Indian blacks in New York was 28% higher than that of native blacks. Sowell concludes: “Neither race nor racism can explain such differences” (p. 33).

The fact that West Indian blacks outperformed native-born blacks certainly presents a challenge for the racism theory, since racism is supposed to affect all people with black skin. But there is no problem for the hereditarian theory, because, again, hereditarianism doesn’t say that all black populations are the same. The obvious explanation for the success of West Indian (and certain other immigrant) black populations is selective immigration. If the most intelligent blacks from the West Indies immigrate to New York, then they may have different outcomes from African Americans for entirely genetic reasons. Sowell doesn’t even acknowledge this possibility.

There is an obvious question that Sowell fails to ask: If West Indian black culture produces such good results in New York, why doesn’t the culture work its magic in the West Indies? Countries like Jamaica and Grenada continue to exhibit results that are consistent with lower average IQ.

When culture follows genes

Sowell “emphasize[s] that the culture which Southerners brought over from the parts of Britain from which they came changed in Britain in the years after they left” (p. 22). The implication is that redneck culture in whites (and therefore in blacks) can’t come from genes. However, he provides no evidence whatsoever for the claim that the cultural tendencies of British rednecks have meaningfully diverged from those of their cousins in America. In fact, Britain in 2024 exhibits similar patterns of regional differences as it did in the eighteenth century. To this day, the Scottish Highlands, Ulster, Wales, and the northern and western uplands of England are notably underdeveloped compared to the areas from which New Englanders emigrated. (The fact that Sowell repeatedly refers to Ulster in Ireland as “Ulster County” hints that he might not have undertaken a thorough investigation of the facts. Ulster County is in New York State. Ulster is a region in the north of Ireland, which encompasses the six counties of modern-day Northern Ireland and three counties in Ireland.) To quote a Guardian article published just a few months ago: “the highest level of wealth exists in the south-east of England, with average wealth per head being £415,200—around £195,400 more than the north’s £219,750.” The poorest counties in Ireland are concentrated in Ulster on either side of the Irish–Northern Irish border. Scotland’s wealth still skews toward the Lowlands, not the Highlands, and Wales has long been one of the poorest parts of Britain.

I don’t want to overplay this point. The relative position of different regions of the UK has shifted somewhat over the decades and centuries. There’s been internal migration and gene flow, which would make it difficult to track the descendants of the populations from which the settlers of the American South were drawn. However, there is no evidence to support Sowell’s suggestion that a population of rednecks in Britain assimilated to the more successful “culture” of its neighbors.

Where does the culture come from?

Sowell proposes an extremely unpersuasive just-so story about the environmental origin of redneck culture (pp. 5–6). The British ancestors of southern rednecks lived in a “world of impotent laws, daily dangers, and lives that could be snuffed out at any moment.” “Prudence and long-range planning of one’s life” didn’t have the kind of pay-off that they would have in “more settled and orderly societies.” Ditto for book learning, business, technology, and science. On the other hand, “manliness and the forceful projection of that manliness to others” ensured one’s personal security in the absence of reliable law enforcement. In other words, a culture of ignorance, improvidence, and violence was (on Sowell’s account) a rational adaptation to environmental conditions. “The kinds of attitudes and cultural values produced by centuries of living under such conditions did not disappear very quickly, even when social evolution in North America slowly and almost imperceptibly created a new and different world with different objective prospects.”

There are at least three obvious objections.

First, until recently, impotent laws and daily danger were the norm in almost all societies. But this did not have the same enduring effect on other populations that it had on British and American rednecks. Millennia of continual threat and uncertainty—culminating in mass violence and genocide—did not produce redneck culture in Jews. In 1953, Koreans emerged from generations of oppression, their country was essentially a giant parking lot, and the average 18-year-old man was 5’5’’ due to malnutrition. Why did Koreans quickly develop a culture of doing math drills for hours a day in hagwon rather than a redneck culture suited to their environment?

Second, if culture adapts to environmental conditions, why can’t rednecks adapt their culture to new conditions? Sowell asserts that “attitudes and cultural values produced by centuries of living under such conditions did not disappear very quickly” when circumstances changed (p. 6). But even on Sowell’s account, redneck values have probably been maladaptive for at least two centuries. It is not explained why rednecks only seem to be able to adapt their culture in one direction.

Third, it is not at all clear that redneck values like imprudence were ever particularly adaptive. Sowell notes that outsiders have often been able to take advantage of opportunities in redneck lands that the natives failed to seize. He writes:

Not only in the South, but in the communities from which white Southerners had come in the Scottish highlands, in Ulster, and in Wales of an earlier era, most of the successful businessmen were outsiders. Even the poorest highland Scots would not skin their horses when they died. Instead, “Scots sold their dead horses for three pence to English soldiers who in turn got six pence for the skinned carcass and another two shillings for the hide.” (p. 21)

If outsiders were well-served by “prudence and long-range planning” even when faced with the same conditions as the rednecks, it doesn’t make much sense to say that rednecks rejected these practices because they didn’t pay.

The world is bigger than America

Perhaps the most fundamental problem with Sowell’s cultural theory of race differences is that it only applies to the descendants of African slaves in the United States. But lower average IQ and socioeconomic status are issues for population-representative groups of Africans all over the world. Just as with “whites,” “blacks” are not homogeneous, and populations vary with respect to traits like intelligence. As discussed, in the US, blacks in some northern states might have had higher IQs than whites in some southern states. Today in the United Kingdom, UK-born black employees earn more than UK-born white employees (though this is largely because they’re more likely to live in London), and in England blacks obtain higher scores than whites on the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE). (In the UK, blacks from the Caribbean have lower incomes and GCSE scores than whites while blacks from Africa have higher incomes and test scores.) But when you compare European vs. African people as a whole, when they are raised under comparable conditions, you tend to find something like a 15–18 point IQ gap. African immigrants to the UK appear to be relatively elite, but it’s not because of their culture. If it were, then Africa itself—which has the benefit of even more African culture—would be a center of education, wealth, and nonviolence, but it is not.

Critique of Hereditarianism

Sowell critiques hereditarianism in his 2013 book, Intellectuals and Race. Unlike many environmentalists, he does not dismiss hereditarianism a priori. He acknowledges that

all races have been subjected to various environmental conditions that can affect what kinds of individuals are more likely or less likely to survive and leave offspring to carry on their family line and the race. Large disparities in the geographic, historic, economic and social conditions in which different races developed for centuries open the possibility that different kinds of individuals have had different probabilities of surviving and flourishing in these different environmental conditions. (pp. 55–56)

However, in Sowell’s view, this remains a hypothetical possibility that cannot be confirmed by science in its present state:

Since there has been no method yet devised to measure the innate potential of individuals at the moment of conception, much less the innate potential of races at the dawn of the human species, the prospect of a definitive answer to the question of the relationship of race and innate mental ability seems remote, if possible at all. (p. 60)

Apparently, Sowell does not think we can get an answer until we devise a method to measure the “innate potential of individuals at the moment of conception,” and maybe even the “innate potential of races at the dawn of the human species” (whatever that means). He seems to have adopted an unreasonably high standard of evidence for hereditarianism, which effectively blocks any possible claim to knowledge on this topic.

In Sowell’s view, a hundred years of psychometrics and behavioral genetics has not only failed to provide a definitive answer to the question of whether there are innate racial differences. He implies that it has taught us virtually nothing about what those differences might be. He mentions the possibility that, at some remote time in the future, science could prove that “the innate mental potential of blacks is 5 percent more than that of whites” (p. 82). In other words, there is currently no scientific basis for speculating on whether a general intelligence advantage lies with blacks or whites.

I claim that the evidence we have today overwhelmingly supports hereditarianism. The case for hereditarianism is particularly strong with respect to the best-studied race gap in the world, namely, the 15–18 point IQ gap between black and white Americans. (This is the gap that Sowell purports to explain with his redneck culture theory.) Hereditarianism doesn’t claim that this gap is necessarily 100% genetic, but that it is substantially genetic, and that stable gaps between other racial groups—particularly those living under comparable conditions—are also likely to have a genetic component.

In his critique of hereditarianism, Sowell (a) focuses on questionable studies from the 1920s and 1930s when the field was in a very immature state, (b) gives misleading accounts of the history of the science, (c) fails to acknowledge strong objections to his claims, and (d) ignores the strongest evidence for the role of genes.

Battle against straw men

Consider the following paragraph:

Progressive-era intellectuals took a largely negative view of the new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, as well as of American blacks in general. Because such a high proportion of the immigrants from Poland and Russia were Jews during this era, Carl Brigham—a leading authority on mental tests, and creator of the College Board’s Scholastic Aptitude Test—asserted that the Army test results tended to “disprove the popular belief that the Jew is highly intelligent.” H.H. Goddard, who had administered mental tests to immigrant children on Ellis Island, declared: “These people cannot deal with abstractions.” Another giant of the mental-testing profession, L.M. Terman, author of the Stanford-Binet IQ test and creator of a decades-long study of people with IQs of 140 and above, likewise concluded from his study of racial minorities in the Southwest that children from such groups “cannot master abstractions.” It was widely accepted as more or less a matter of course during this era that blacks were incapable of mental performances comparable to whites, and the Army mental test results were taken as confirmation. (p. 26)

Pretty much everything in this passage is wrong or misleading.

First, regarding Brigham’s statement about Jews, Sowell repeatedly emphasizes the claim that intelligence researchers in the early twentieth century thought that Jews had lower average intelligence. But, in later generations, Jews would score well on IQ tests, and Jews were wildly overrepresented among leading scientists. For Sowell, this shows that there is no reason to take the current rank-ordering of intelligence seriously, since the ranking can shift dramatically in a short period of time. “Radical changes in the relative rankings of Jews on mental tests between the period of the First World War and their very different rankings in later years undermined belief in the permanence of group and intergroup IQ levels” (p. 85).

Note that Brigham’s quote, which comes from a book published in 1923, acknowledges that Jews were already stereotyped as “highly intelligent.” Brigham made the mistake of putting his faith in a flawed test given to people who didn’t have the linguistic and/or cultural background to be properly assessed. There is no indication that anyone besides Brigham (and some obviously biased anti-Semites) made this mistake. Indeed, an influential psychology textbook published in 1931 in Germany observed: “When we compare the average German Jew with the average German Gentile we cannot doubt that the Jews greatly excel in intelligence and alertness.” Snyderman and Herrnstein note that Brigham’s book was panned in reviews published in 1923 in Science and Scientific Monthly, and in an article published in Mental Hygiene in 1924. Furthermore, as Sowell acknowledges in another passage, Brigham himself “said candidly in his 1930 article that his previous conclusions were...‘without foundation’” (p. 72). The full quote from Brigham’s 1930 article is an almost unprecedented admission of error:

This review has summarized some of the more recent test findings which show that comparative studies of various national and racial groups may not be made with existing tests, and which show, in particular, that one of the most pretentious of these comparative racial studies—the writer’s own—was without foundation.

Far from discrediting intelligence research, this incident displays a remarkable open-mindedness and capacity for self-correction after a false start. Sowell’s comment that “statistical data that seemed to fit prevailing preconceptions among intellectuals have been accepted and proclaimed, with little or no critical examination” (p. 73) is grossly unfair.

Second, regarding the Goddard quote that immigrant children “cannot deal with abstractions,” this is a complete misrepresentation. Goddard claimed to show that immigrants who were “feebleminded” or “morons” (to use the technical terms of the time) could be identified more efficiently and accurately by administering the Binet scale rather than by laboriously interviewing them. Goddard’s comment about children who “cannot deal with abstractions” was meant to apply to morons, not to immigrants in general or to any races specifically. As Goddard noted: “Our study...makes no attempt to determine the percentage of feeble-minded among immigrants in general or even of the special groups named—the Jews, Hungarians, Italians and Russians.”

Third, attributing the view that minority children in the Southwest “‘cannot master abstractions’” to Terman is another misrepresentation. In this context, Terman was commenting on the limitations associated with “border-line deficiency.” He said that border-line deficiency was far more common among certain races, including blacks, but he did not claim that all members of any race were deficient in this way. He called for race differences to be investigated “anew and by experimental methods,” and he predicted that “there will be discovered enormously significant racial differences in general intelligence, differences which cannot be wiped away by any scheme of mental culture.” His politically incorrect (and exaggerated) language notwithstanding, Terman’s prediction has largely been supported by subsequent investigation.

The stability of race differences

Sowell argues that “there is nothing unique about the average black American IQ of 85,” since “at various times and places” other groups had IQs in the same range. He cites a 1923 survey of studies of the IQs of Italian Americans, which found scores ranging from 77.5 to 85. A 1926 survey of studies of the IQ of different groups in America found means of “85.6 for Slovaks, 83 for Greeks, 85 for Poles, 78 for Spaniards, and 84 for Portuguese” (p. 72). The implication is that the scores of different populations fluctuate wildly across the generations, and therefore the African American IQ of 85 may shoot up to 100 at any moment. But the African American IQ of 82–85, which has been stable for cohorts born since around 1970 and has resisted intensive interventions, does not have the same status as scores from flawed IQ tests administered a hundred years ago to immigrants who may not have been fluent in English.

In Facing Reality, Charles Murray reported a 0.85 standard deviation gap in cognitive ability between black and white Americans. But this was only because his analysis included academic achievement tests. Actual IQ tests continue to show a 1 to 1.2 standard deviation difference.

Mixed-race children

Continuing to build his case largely on old and dubious data, Sowell cites the famous study of illegitimate children born during the American occupation of Germany after World War II. These children were (according to the story) fathered by either white or black American soldiers and raised by their German mothers. Intelligence testing found no statistically significant difference in the IQs of a sample of 83 white vs. 181 biracial kids from this population. Sowell approvingly cites James Flynn’s conclusion that “the reason for results being different in Germany was that the offspring of black soldiers in Germany ‘grew up in a nation with no black subculture’” (p. 75).

Sowell fails to mention three important facts about this study, which are highlighted by John Loehlin et al.

First, 20 to 25% of the “black” fathers weren’t African American or even black, but were French North Africans who would normally be classified as white.

Second, subjects were tested as young children. At the time of testing, a third were between age 5 and 10, and two-thirds were between 10 and 13. (Sowell doesn’t mention that the subjects were children, referring to them as “the offspring of black and white American soldiers.”) The heritability of IQ is much lower in children than adults.

Third, black American soldiers during the Second World War were relatively elite. 30% of blacks were rejected for military service due to their scores on the pre-induction intelligence test compared to just 3% of whites. Loehlin et al. note that even after this selection there was still a one standard deviation gap between black and white inductees’ average scores on the Army General Classification Test. However, there was certainly a significant environmental component to this gap, as blacks born in the 1920s did not achieve their cognitive potential. (The black–white IQ gap narrowed steadily until the 1970s.) Loehlin et al. do not perform this calculation, but we can estimate the average IQ of black vs. white soldiers in WWII. Assume American blacks and whites had the genetic potential on average to attain IQs of 85 and 100, respectively (with SD = 15). If the Army General Classification Test was a perfect IQ test and 30% of blacks and 3% of whites were disqualified, the black soldiers had an IQ cutoff of 77, while white soldiers had a cutoff of 72. The average IQ of black vs. white soldiers would have been 93 vs. 101—a difference of 8 points.

Why does James Flynn think that the German study supports a cultural theory of the black–white IQ gap? Flynn is aware of the issues I mentioned above, and unlike Sowell he does not base his argument on the mere fact that the white and biracial children had the same IQs. Rather, his argument is based on a fact about the statistical pattern of the scores of the children, namely, the magnitude of the black–white gap isn’t correlated with the g-loading of the subtest as it normally is among whites and blacks in the US. I won’t comment on this argument except to say that when you have to rely on a small, old study with many unknowns, that does not reflect well on the strength of your position.

Flynn effect to the rescue?

Flynn is most famous for his role in discovering the “Flynn effect.” This refers to the steady, worldwide rise in raw IQ scores over the course of the twentieth century. IQ tests are continually re-normed to keep the average at 100, which hides the fact that test takers (both black and white) are answering more and more questions correctly. A raw score that would give you an IQ of 85 in 2024 would have corresponded to an IQ over 100 in 1950. In other words, African Americans today would outscore American whites if they were transported far enough back in time.

Sowell argues:

While the persistence of a gap between blacks and whites in America on IQ tests leads some to conclude that genetic differences are the reason, the large changes in IQ test performance by both black and white Americans, as well as by the populations of other whole nations around the world, undermine the notion that IQ tests measure an unchanging genetic potential.

This is correct in a sense, but it doesn’t support environmentalism about race differences in the way Sowell implies. Yes, there is some environmental factor that varies across generations and influences IQ scores. Probably this is a cultural zeitgeist that increasingly promotes the kind of scientific way of thinking that is rewarded by IQ tests. But this does not necessarily tell us anything about the source of variation within generations. The fact that the average Jew today is taller than the average Dutchman a hundred years ago doesn’t mean that Jews have the same height potential as the Dutch. Under comparable conditions, the Dutch will probably always be taller (on average). Flynn himself does not believe that his eponymous effect explains race differences, and he approvingly cites Arthur Jensen describing his position: “[Flynn] believes that IQ gains show that blacks can match whites for IQ; but he does not believe that they can show that blacks can do this when environments are equal.”

Ignoring evidence

Sowell flat-out ignores the strongest evidence for hereditarianism. He doesn’t say a word about the substantial differences in brain size among races, which track differences in IQ (African << European < East Asian). Although he notes that black children adopted by white families have “higher average IQs than other black children” (p. 79), he doesn’t mention that this advantage fades out by early adulthood, when IQ has a much higher heritability. He doesn’t mention the fact that blacks and whites regress to different means. African Americans whose parents make more than $200,000 a year score lower on the SAT than whites whose parents make between $20,000 and $40,000, which is exactly what we would expect if the differences were rooted in genetics rather than the environment. He doesn’t discuss intensive intervention studies, such as the Milwaukee Project, that have had extremely disappointing results. (This is not to mention the more recent evidence from genetics, which wasn’t available when Sowell’s book was published in 2013.) Clearly, Sowell has not given hereditarianism a fair shake.

SAT scores (out of 1,600) by race and household income in 2008. From the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education.

Politically Unhelpful

If I am right, hereditarianism remains the best explanation for intractable differences between—and in some cases within—racial groups. Cultural differences often emanate to some degree from differences in biological endowment. A population with an average IQ of 85 (whatever its racial composition) is likely to produce a culture with different features than a population with an average IQ of 100 or 105. To the extent that culture is responsible for group disparities, it may have this effect by reinforcing the tendencies that gave rise to the culture in the first place.

Some conservatives and classical liberals have argued that we can defeat wokism by promoting Sowell’s theory, regardless of whether or not it’s true. This is a big mistake.

As I have explained elsewhere, wokism is what follows from taking the equality thesis seriously, given certain widely accepted moral premises. If you think that all populations literally have the same innate potential, and yet they have very unequal outcomes, there is a moral emergency to correct the environment to uplift lower-performing groups. In practice, disparities favoring whites will be blamed on past or present white racism, and this puts us on an inexorable path to DEI dystopia.

Even if, hypothetically, we could convince people to accept Sowell’s false cultural theory of race differences, this would simply be an indirect route to wokism. Sowell insists that his cultural theory provides an “alternative” to “blam[ing]...the sins of others, such as racism or discrimination” (BRWL, p. 62). But if his theory is right, then white people are still responsible for imposing redneck culture on Africans in the first place, and for creating conditions in which it is able to persist. In fact, Sowell himself blames “white liberals” who “excuse, celebrate, or otherwise perpetuate that lifestyle” and “contributed to its spread up the social scale to middle class black young people who feel a need to be true to their racial identity” (pp. 63–64). My point is that as long as disparities are attributed to the environment, regardless of whether you point the finger at racism or “culture,” someone is going to be held morally responsible. Sowell and his Hoover Institution and National Review friends want to place the blame on white liberals. That would be preferable to blaming all people with white skin, but this strategy does not have a serious political future.

Whether or not it would be politically advantageous to trick people into accepting Sowell’s false theory of race differences is a moot question. Conservatives have been pushing this idea for decades, and people have rejected it. The empirical evidence clearly shows that few people find Sowellism persuasive.

This leaves hereditarianism as both the correct theory of race differences and the only intellectual weapon capable of seriously challenging the left’s narrative about race. We have two choices: promote hereditarianism and have a chance of winning, or accept that our fate is to complain about woke excesses in webzines and on X while wokesters consolidate their power.

Addendum (October 19, 2024)

No one has yet pointed out a single error in my analysis. In fact, responses in the past two months have raised even more serious questions about Sowell’s scholarship, particularly in regard to his extraordinary claims first made in his 1974 paper, “Black Excellence—The Case of Dunbar High School.”

Dunbar was an all-black high school founded in 1870 in Washington, DC. According to Sowell, it achieved miraculous results via the pull-your-pants-up-and-show-some-respect strategy favored by mainstream conservatives. (In his words, the school was “frank in telling the black community that it would have to send its children to school with respect for teachers and a willingness to submit to discipline and hard work.”) He says that although “Dunbar students were not selected on the basis of I.Q. tests,” the average IQ of students at the school was above the white mean, and in some years as high as 111. He repeats these claims in Black Rednecks and White Liberals (2005) and Intellectuals and Race (2013), although in the latter book he for some reason drops the claim about the students having an average IQ of 111.

Anyone familiar with intelligence research knows that such results are unprecedented. If what Sowell reports is even 50% true, it would radically alter our understanding of intelligence, heritability, race, and society.

Is it true? Todd Shackelford and Bo Winegard made an intensive effort to track down the source of Sowell’s Dunbar IQ data, and they came up empty handed.

I’m not insinuating that Sowell did anything untoward. But I believe we should know more about the provenance of the data before we take his claims about Dunbar at face value. If anyone has information about this—or is in contact with Sowell and can ask him for the full story—please let me know.

There are other, more minor misrepresentations. A couple weeks ago, someone mentioned Sowell’s claim in Race and Culture that Cicero thought that Britons were “stupid.” (The point is supposed to be that the ranking of groups by intelligence changes radically over time, ergo we shouldn’t put much stock in the current rank order.) I was already familiar with a fake Cicero quote roasting Brits, and I figured that this is what Sowell was referring to.

Sowell writes:

Cicero warned his fellow Romans not to buy British slaves, for he found them unusually difficult to teach....Cicero warn[ed] ancient Romans not to buy British slaves because of their stupidity....

What Cicero actually said:

I fancy you won’t expect any of them to be highly qualified in literature or music.

A completely different statement, which doesn’t support the argument Sowell was making. Not the biggest issue in the world, but this kind of thing comes up again and again.

A couple lessons:

First, no one should write 60 books. (10 out of the 60 are revised editions, but my point still stands even if you call it 50 books.) No matter how smart you are, it is impossible to maintain high standards given this level of output. The fact that Sowell is encouraged to publish a book every year is a systemic failure.

Second, too much praise can be harmful. Sowell’s talent is undeniable, and he has done great things. But for decades he has been surrounded by people who, instead of subjecting his arguments to critical scrutiny, immediately laud him as a historic genius every time he utters a sentence. I believe Sowell is to some extent a victim in this situation. If he had been treated as an equal and forced to defend his ideas like the rest of us, he could have reached greater heights.

I've sometimes wondered why nobody capable has ever taken apart Thomas Sowell's, and various others', claim that hereditarianism counts for almost nothing. Well, I need wonder no more. I couldn't have asked for a more comprehensive demolition.

In critiquing hereditarianism in Intellectuals and Race, Sowell's citation of the low IQ of WWI Irish conscripts is particularly noteworthy.

On this point Sowell remarks that 26 percent of Irish soldiers exceeded the overall American norm as did even fewer percentages of ethnic Russians (19%), Italians (14%) and Poles (12%). However, the citation to Brigham (1923) largely (if not fully) reports results from an Irish sample consisting of 658 observations (see Table 9 of Brigham (1923)); it seems that these likely encompass the 422 Army Alpha, 205 Army Beta and 25 Stanford-Binet test takers first assembled by Yerkes (1921) (see Russell Warne's discussion of this study here: https://russellwarne.com/2022/12/17/irish-iq-the-massive-rise-that-never-happened/). Importantly, as Warne notes in his review of past Irish IQ estimates, "The two lowest scoring American samples were both from data collected during World War I and reported by Yerkes (1921): 205 illiterate, foreign-born Irish draftees taking the Army Beta (avg IQ = 80.9) and 25 low-functioning foreign-born Irish draftees taking the 1916 Stanford-Binet (avg IQ = 77.4). Both of these samples are clearly not representative of the general Irish population. Removing these individuals increases the American Irish weighted mean to 97.8." That is, about a third of Sowell's Irish sample consists of illiterates whose verbal IQ scores are therefore of dubious validity.

The scatterplot in Warne's blog clearly shows that historic Irish IQ has likely always been about 98, contradicting claims of a massive, environmentally-mediated IQ rise in this (and likely all other) ethnic groups.