Are Smart People Superior? A Reply to Noah Carl and Charles Murray

The capacity for “human worth” is not distributed equally

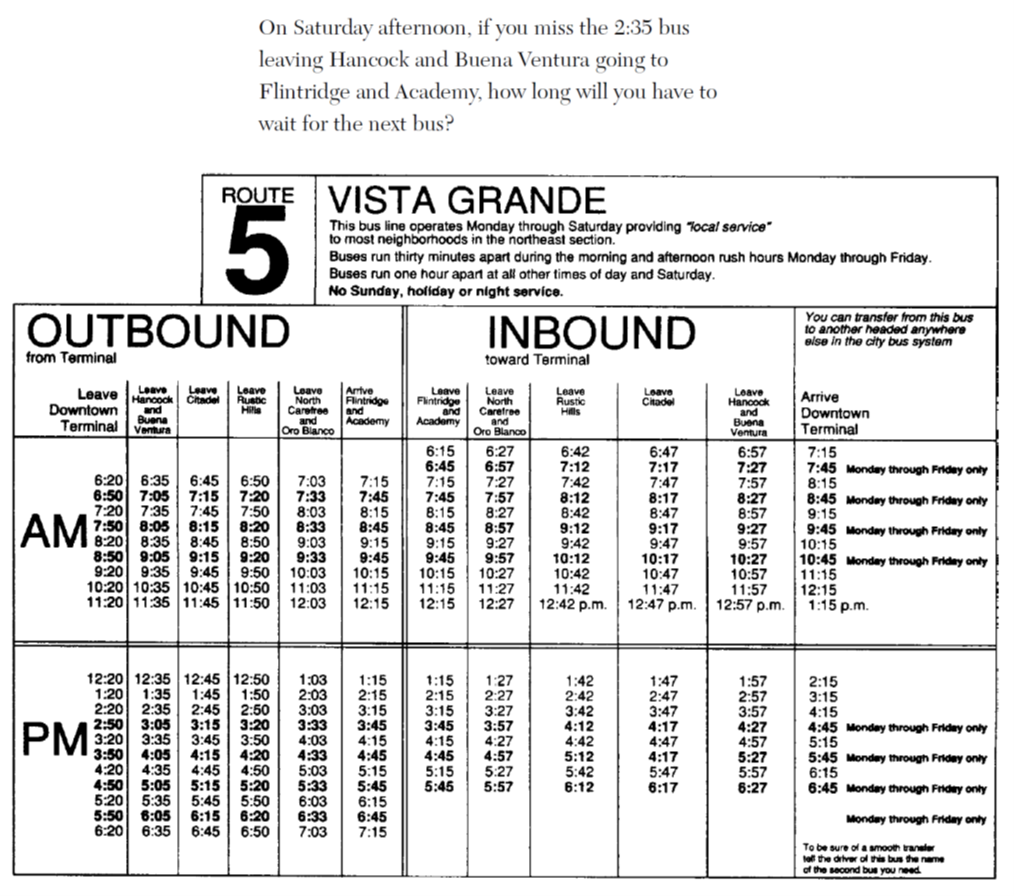

77% of (white) adults cannot reliably use a bus schedule to figure out how long they would have to wait for a bus traveling from one city to another. Meanwhile, other members of the species are drawing up plans to colonize Mars. Part of the difference between these groups is their luck in the genetic lottery. People are born with more or less potential to grow gray goo in their skulls or produce thick myelin sheaths around their neuronal axons. No amount of vitamin supplementation, universal pre-K, or programs to boost self-esteem can entirely correct for nature’s unfairness.

Hereditarians who point out these facts are often accused of thinking that people with less intelligence are morally inferior or that IQ is a measure of human worth. Charles Murray dismisses these charges as nonsense. In his 2020 book, Human Diversity, he writes that “it is obvious how senseless it is” to conflate “intellectual ability and the professions it enables with human worth....There shouldn’t be any relationship between these things and human worth.”

Noah Carl defends Murray’s view, and criticizes arguments made by Emil Kirkegaard, Stephen Kershnar, and me. Kirkegaard writes: “Moral worth correlates with intelligence (and other traits).” Kershnar argues that “intrinsic moral value is proportional to autonomy,” which in turn is “proportional to intelligence.” I claim: “Less intelligent people are inferior...in some respect. Everyone has ‘human dignity’, but if two people are drowning and I can save one I’d consider relative intelligence (among other things).” Carl rejects these ideas, and concludes that “Murray is right. IQ is not the same as moral worth and it’s a mistake to treat it as such.” Murray reposted Carl’s article and declared himself to be “baffle[d]” by Kirkegaard and me.

But Carl’s argument misses the mark, and Murray’s bafflement is misplaced. We should not be squeamish about acknowledging a connection between intelligence and “worth,” although the nature of that connection needs to be spelled out.

Sample problem from the National Adult Literacy Survey (Document Level 4). 77% of white American adults cannot reliably answer this question.

Sample problem from the National Adult Literacy Survey (Document Level 2). 16% of white American adults cannot reliably answer this question.

Human Worth, Moral Worth, and Inferiority

Murray and Carl do not define the terms “human worth” or “moral worth.” What could they be referring to?

Start with the idea of “moral worth.” Moral realism is the theory that there are objective, mind-independent moral facts. A proposition like “it’s wrong to shoot random people for fun” is true in the same way as 2 + 2 = 4 is true. If you’re a realist, you might say that an individual’s “moral worth” is a function of their relationship with the true morality. Perhaps moral worth corresponds to the purity of a person’s will, the perfection of their character traits, or the amount of good that they actually accomplish.

In my view, moral realism is an illusion. Our intuitions about right and wrong are the product of morally blind evolutionary and cultural forces. There is no reason to think that our moral beliefs correspond to an independently existing reality. Furthermore, moral realism is conceptually incoherent. I have no idea what it would even mean for there to be objective truths about how we’re supposed to think and act. Any concept of moral worth that is predicated on moral realism can be dismissed.

If moral realism is false, there are two options. Either we can reject morality (and therefore the concept of “moral worth”) as a myth, or we can interpret morality non-realistically. I favor the latter. The institution of morality, when stripped of illusions, serves a useful function. It is a vehicle to express collective values. Judgments about what is “right,” “wrong,” “just,” “unjust,” “good,” or “bad” are not mind-independently true or false. They are evaluations made in accordance with the conventions of a community. “Moral worth” is a measure of what we value, all things considered, in an agent, object, or situation.

What does Murray mean by “human worth”?

Perhaps he would argue that “human worth” is the intrinsic value we possess in virtue of our species membership. Philosophers call this view “speciesism.” As Peter Singer notes, the term is meant to invoke offensive “isms” like racism and sexism. But speciesism has defenders. Bernard Williams asks how we would respond to extraterrestrials who, having correctly judged us to be cognitively inferior and emotionally impoverished, decided to exterminate earthlings for the good of the universe. Should we submit to our own genocide in order to make way for a species that is superior to us with respect to everything that we care about except species membership? Williams defends the “human prejudice.” We make judgments from our own perspective, and there’s no rational basis for objecting to a bias in favor of ourselves. Singer rejects this argument, noting that we would not accept the same style of reasoning if it were applied to race. My own view is in between those of Williams and Singer. On the one hand, there is no law of reason that stops us from being partisans for Team Human. On the other hand, speciesism is an arbitrary way of assigning worth from the perspective of what we normally take to be relevant. If a parrot or an alien starts speaking to me as a rational, emotionally sensitive being, I will treat it as a person. If it displays a good and noble character, I will probably respect it more than a bipedal earth ape without these qualities.

Suppose Murray rejects speciesism but argues that “human worth” stems from properties that are statistically associated with Homo sapiens such as self-awareness, the ability to plan, or moral sensitivity. (Presumably he wouldn’t say “intelligence,” although virtually every other candidate property—including the ones I just listed—would depend on intelligence.) In that case, people probably vary in how much of the worth-giving properties they possess. The distribution might overlap with that of some other species. Thus, so-called “human worth” would not be universal in humans (at least it wouldn’t be possessed to the same degree by all of us), nor would it be distinctively human. A magpie that can recognize itself in a mirror and grieve the death of its friends would probably surpass a coma patient, a psychopath, or a severely mentally disabled person with respect to one or more of the special properties.

One could argue that “human worth” is a threshold concept: you have human worth if and only if you have X, and intelligence beyond what is necessary for X does not confer extra worth. But there is no indication that Murray would want to take this position. He says that higher intelligence is irrelevant to human worth, not that all humans have the same worth. So he should accept the possibility that human worth varies, and that this variation might be correlated with differences in intelligence.

What does it mean to say that someone or something is “inferior”? Carl appears to treat this term as equivalent to “less moral worth.” But a judgment of inferiority is relative to a standard of evaluation. It makes no sense to say that “A is inferior to B” without specifying the standard in question. A smart person is superior to a dumb one with respect to the ability to do calculus. But they are inferior with respect to the ability to be entertained by chanting “Jerry! Jerry!” while hillbillies brawl on a stage after getting the results of a paternity test. In some cases, the standard of evaluation is not stated explicitly, but can be inferred from the context. If we’re talking about sports, philosophy, or music, our judgments are relative to the standards in those different fields. “Kevin Love is inferior to LeBron James” obviously means he’s not as great a basketball player. “Kevin Love is inferior to Woody Allen” doesn’t mean anything unless you explain what the standard is.

Operationalizing “Human Worth”

I’ll focus on the general notion of “human worth.” Once we have a grasp of human worth, we can ask how someone can be inferior or superior with respect to this standard.

There are two kinds of value: intrinsic and instrumental. In other words, X can be valuable in itself, and/or because it is part of a chain of causes that leads to something that is intrinsically valuable. Money is valuable because of what it can be used for: buying things, acquiring social status, or the like. Its value is instrumental. On the other hand, pleasure has (at least under certain conditions) intrinsic value. We value our own pleasure and that of (worthy) other people as an end in itself.

“Human worth” must be a function of properties that have intrinsic and/or instrumental value. The question is whether intelligence could be among these properties, and whether variation (at least within the normal range) could have significant implications for the relative standing of individuals.

Let’s consider how to operationalize the concept of X having value in the context of human worth. You might:

pay a cost to preserve X (in yourself or others) even if you don’t expect X to produce anything else that you value

pay a cost to preserve X (in yourself or others) because you think X will lead to desirable effects

choose X over not-X in the context of embryo selection, all else being equal

rescue a drowning X-possessor over a not-X-possessor, all else being equal

blame people for not having X

praise people for having X

High intelligence clearly satisfies some if not all of these conditions.

Part of what makes humans more intrinsically valuable than other animals is our superior capacity to understand, contemplate, plan, have an identity, and (as Kershnar highlights) exercise autonomy. All of these things are rooted in intelligence. Presumably that’s why Peter Singer avers that “The most obvious candidate for regarding human beings as having a higher moral status than animals is the superior cognitive capacity of humans.” The more intelligence you have, the greater your potential to manifest what is intrinsically valuable. This is one of the reasons why, for example, we would hesitate to take a drug that permanently impairs intelligence even if the drug would have some benefit.

When it comes to instrumental value, intelligence is the composer and the conductor. It is the basis of virtually all successful action. It is the power that wields every other instrument. By the exercise of intelligence we obtain food, cure disease, confine our natural predators to cages, and read a bus schedule. One day (we hope) it will allow us to build megaprojects, colonize the galaxy, and escape our dying star. We value intelligence, and do our best to cultivate it, in part because of these extrinsic benefits.

When performing IVF, it is now possible to sequence the genome of different embryos to choose the one with the most desirable combination of expected traits. With the current technology, when choosing among ten embryos, there will be an expected difference of about 12 IQ points between the lowest and the highest. IQ is not the only trait we care about. But, when choosing between different possible lives, any informed person would consider intelligence, among other traits.

If two people are drowning and you can only save one, commonsense “morality” does not demand that you make the decision by a coin flip. The convention is to save women and children first. All else being equal, we value the lives of women over men, and the lives of children (who have more potential life) over adults. All else being equal, we save a parent over someone without dependents, because the former’s death would cause more aggregate suffering. Since intelligence has both intrinsic and instrumental value, the relative intelligence of the drowning victims should also be part of our calculation. Obviously, that doesn’t mean intelligence automatically trumps everything else. If Jeffrey Epstein’s yacht is sinking, we would save Epstein last even though he probably has a higher IQ than most of the sailors and waiters.

Theoretically, we can only praise or blame people for outcomes that are under their control. (I leave aside the philosophical question of what it means for something to be under your control.) Within developed societies, IQ is largely fixed by genes and random developmental factors. No one is responsible for being born with a particular polygenic score for IQ, or for the random ways in which their nerve cells differentiate. For the most part, we don’t praise or blame people merely for being born bright or dim.

But intelligence—or at least the expression of intelligence—is to some extent the result of our choices. E = mc2 wasn’t encoded in Einstein’s genome, growing out of him like a limb. He chose to study science and exert himself rather than doing the early 20th-century equivalent of watching TV. Ditto for all intellectual accomplishments, great and small. This is part of the reason why we praise people for displaying intelligence. Conversely, we might blame someone for failing to live up to their intellectual potential due to their choice to be a drunk, a sloth, or a grifter.

We also blame people for manifesting their natural stupidity by choosing to do something offensive—for example, arguing about something they don’t understand, or occupying a position of influence for which they are not qualified. Thus, we might call a low-IQ Internet commenter, an incompetent politician, or a not-so-bright professor an “idiot” in an insulting way. This can be justified on the grounds that the offending person made the choice to strive for something for which they had no natural right. There’s nothing blameworthy per se about the Jacob Urowsky Professor of Philosophy at Yale Jason Stanley getting an SAT score of 1280, which is more than a standard deviation above average. We insult Stanley for his intelligence when he poses as a great intellect with the authority to pass judgment on everyone else.

There is an element of cosmic unfairness in praise and blame. We don’t build statutes for all of the hundreds of thousands of scientists who worked just as hard as Einstein and with equally noble intentions, but failed to accomplish as much as he did. We don’t give the Medal of Honor to every soldier—let alone every person—who would rescue his comrade in the face of danger, but who never had the chance to do so. When it comes to blame, we do not hang everyone who would have been a vicious concentration camp guard if only he had the moral misfortune of being born in Dachau in 1905 and offered the job. And even if we did, this would not correct for the world’s cosmic unfairness. The innate potential to be a genius, a hero, or a criminal is itself the result of luck. Nevertheless, this is the logic of praise and blame.

Calculating Human Worth

There is no formula for calculating “human worth,” and no objective standard that tells us how to weigh different values. But I suggest the following general principle holds: all else being equal, more of a worth-giving property (whether it has intrinsic and/or instrumental value) imparts greater aggregate worth.

When it comes to intelligence, Carl and Murray agree that some people are objectively better than others. As Murray puts it, “ability varies” and “half of the children are below average.” Someone who can remember only 5 digits is inferior to someone who can remember 11 digits vis-à-vis the standards associated with that cognitive task. If the words in question are understood in their usual senses, my original claim, which Carl took issue with, that “less intelligent people are inferior...in some respect,” cannot be intelligibly denied. If intelligence is a worth-giving property, all else being equal, smarter people have more worth.

Carl trumpets the fact that the top government officials in Nazi Germany were highly intelligent. The average IQ among 21 Nazi leaders who were tried at Nuremberg was 128. As Carl puts it, “Despite these men’s high IQs, their moral worth was far from exceptional,” and the guilty ones may have had “little or no moral worth” at all. This is certainly true. But who does Carl claim to refute with this example? Does he refute Kirkegaard? Kirkegaard says that “Moral worth correlates with intelligence (and other traits).” To say that there is a correlation between X and Y does not mean that X and Y are the same thing, or that it’s impossible to have cases where a high level of X is associated with a low level of Y. Kershnar says that “other things equal, intrinsic moral value is proportional to intelligence....[I]t is possible that a person with great autonomy uses these capacities while acting wrongly.” He goes on to say that “There are other plausible grounds for intrinsic moral value in persons,” including “moral goodness (i.e., the moral nature of one’s character and acts).” Again, I say that the less intelligent are “in some respect” inferior. I leave open the possibility that a less intelligent person can be in some respect superior, or that they can have more all-things-considered worth.

Any instrument can be used for bad purposes. In practice, intelligence is more often employed for good. As documented by Garett Jones, most high-IQ countries are not Nazi dystopias. They are on average wealthier, more cooperative, and less corrupt. Whether morality is construed realistically (which would be an error) or non-realistically, moral reasoning requires intelligence. No matter how well-meaning they are, those who are unintelligent have less ability to reason through moral dilemmas, understand morally relevant facts, and evaluate moral trade-offs.

Intelligence isn’t one-dimensional or equivalent to “IQ.” But some people intellectually outperform others in virtually every way. On average, higher IQ corresponds to greater ability across the board. This has implications for both the kinds of good you can and are likely to accomplish (your instrumental value) and the kind of good that you instantiate (your intrinsic value).

There are many routes to “human worth,” and ways to achieve greatness that do not require a stratospheric level of general intelligence. George Motz has devoted his life to the study of hamburgers. He is the grill master of his own burger shop in New York, where he makes the most historically authentic, traditional American hamburger. I don’t know what his IQ is. It’s probably well above average, though I doubt it’s off the charts. Yet, when it comes to “human worth,” in my view, Motz ranks among the elites. He is far superior to Chris Langan—the conspiracy theorist and philosophy crackpot who supposedly has the highest IQ in the world.

Grill master George Motz exhibits far more worth than most philosophy professors

Superiority (with respect to overall worth) does not depend only on the kinds of accomplishments that make headlines. Raising a family, keeping a promise, making money, or perfecting your character can also confer high levels of worth. As my ancestor King Solomon said, “he who rules over his spirit is better than he who conquers a city.” There can even be greatness in failure.

Diversity itself can be intrinsically valuable. We think the extinction of the dodo bird was sad despite the fact that the dodo was probably dumber than a pigeon, with no special redeeming quality. A person’s contribution to diversity can also count toward their intrinsic worth. The special adaptations of different populations or the unique features of individuals are potentially worth-giving properties, all the more so the rarer they are.

John von Neumann was the quintessential high-IQ genius. With his computer-like brain, he revolutionized mathematics, physics, computer science, and economics. Charles Murray likes to challenge people who think intelligence is connected to human worth, saying, Do you think von Neumann was more valuable than you? A “yes” answer is supposed to be unthinkable, so the interlocutor is offended into accepting the claim that high intelligence doesn’t confer extra value.

But this is a rhetorical trick. Of course most people value themselves more than a stranger with a higher IQ—or even a stranger who is superior to them in every important way. As Bernard Williams said, we make value judgments from our own perspective. There is no objective stance, or point of view of the universe. Being me confers value for me. My friend is more valuable to me than a stranger, perhaps even a stranger who is, according my own value system, superior to them in every respect except for not being my friend. The fact that what is valuable to me depends on my personal interests says nothing about whether intelligence is a worth-giving property.

A better question would be, Do you think von Neumann was more valuable than a random person? Now the value of intelligence shines through. Obviously the answer is “yes.”

Carl says that “It may be reasonable to argue that, all else being equal, higher IQ equates to greater moral worth—though this is true of all socially valued traits, so there’s nothing special about intelligence.” This concedes everything. According to Carl, if you hold all else equal, the person who is smarter is more valuable in a “moral” sense. In real life all else is usually not equal, and there are other factors to consider besides intelligence. But no one denies this.

Political Equality

Kershnar suggests that, intuitively, it seems that the interests of those of greater “moral worth” should count for more. Should we create a caste system, granting special privileges based on worth or characteristics known to be associated with it such as intelligence?

The egalitarian might assert that, although technically we are not equals in terms of worth, we are equal in some other sense. Perhaps we are political equals, or “equal under the law.” Or, despite having different degrees of worth, there is some moral sense in which we are equal.

In political philosophy, the principle of “human equality” is often taken for granted, but rarely elucidated. Liberal legal philosopher Jeremy Waldron observes: “Among those who make use of some very basic principle of human equality, virtually no one has devoted much energy to explaining what the principle amounts to in itself.” Uwe Steinhoff highlights the fact that Waldron only complains about the failure to clarify the principle of human equality, not the failure to justify it. Waldron does not seem to think that the principle requires justification. For him it is just obviously correct. Waldron explains why philosophers hold their nose at the prospect of clarifying the principle of human equality:

No doubt part of the reason for reticence here has to do with the unpleasantness or offensiveness of the views—sexist and racist views, for example—that one would have to pretend to take seriously if one wanted to conduct a serious examination of these matters.

It is unclear why a critical examination of the principle of “human equality” would require one to take “sexist and racist views” seriously. Those who deny “human equality”—whatever that is supposed to refer to—needn’t claim that ancestry or sex per se make people unequal. There can also be inequality within a race or sex.

Some critics see the principle of political, moral, or human equality as a contentless tautology. Legal philosopher Peter Westen refers to the “empty idea of equality.” People can only be equal with respect to a rule or principle. But the rule itself already tells us how to treat people. The declaration of equality adds nothing. Suppose there’s a law that says, “if you drive without a license, you must pay a fine.” Then I come along and say, “we’re all equal under the law.” What have I added to the law? The law specifies who has to pay the fine under what conditions. Saying that we’re all equal under the law, or that the law has to be applied equally, is the same as saying “you have to follow the law.”

On the other hand, if the assertion of political or moral equality is treated as the substantive, nontautological claim that everyone should have “equal respect and concern,” then it is blatantly false. At least it’s something that no one genuinely accepts. As Steinhoff notes, we do not owe a vicious criminal and his victim “equal respect and concern.” But, to be fair to the egalitarians, perhaps all they mean is that “persons initially owe all other persons equal respect and concern, but not after they have made different and perhaps immoral choices.” Steinhoff retorts that, “if that is really all they mean, then that should be all they say.” If that is what they choose to say, they are probably still wrong. A mother is free to be partial to her own children.

I think there is a meaningful sense in which we can be considered political equals. It’s not because we’re “equal under the law” (a tautology), but that the law ignores certain differences between people that might otherwise be relevant. Theoretically, desert is proportional to worth. But there are limits to how much the law tries to distribute rewards in accordance with that criterion. Whether you are entitled to a tax refund does not depend on whether you have a low or high IQ, whether you’re a jerk, or how autonomous you have. If a private individual were giving away money, perhaps they would consider these things. But the law deliberately blinds itself to certain considerations. In the context of most laws, we are (almost always) treated as if we had the same level of intelligence.

Accepting the Hierarchy

Murray complains that “no one tells high-IQ children explicitly, forcefully and repeatedly that their intellectual talent is a gift. That they are not superior human beings, but lucky ones.” My message to high-IQ children is different: “You were born into the natural aristocracy. You have an obligation to strive for the greatness of which you are capable. Your moral superiority is not guaranteed by your score on an IQ test. If you fail to reach the summits to which nature has equipped you to ascend, your ignominy is as great as your squandered gifts. And so is your culpability if you misuse your talents to destroy or oppress.”

The egalitarian ethos is epitomized in the false declaration that “all men are created equal.” The hereditarian says what every sensible person already knows to be true, namely, that there is a natural hierarchy for everything. Coming from a background of Christian egalitarianism, we hesitate to state the truth so nakedly. The task is to align our moral intuitions with the truth of hereditarianism.

Thanks for writing this response. I think we agree about a lot, while emphasising different things. I want to emphasise that intelligence is only one contributor to moral worth, which can be outweighed by other considerations. I also want to emphasise that there's nothing special about intelligence. For example, one could write similar articles on why people with higher conscientiousness or pro-sociality have greater moral worth. Meanwhile, you want to emphasise that intelligence is an important contributor to moral worth, and we shouldn't downplay that.

Eugenio Proto's study says intelligent people are socially competent. If moral worth is conditional on favourable social traits, then intelligent people are morally superior